Of the five or six most well-known charting packages, none really impressed me (being a devoted user of Highcharts, in Javascript). The exception to this is plot.py but it’s a remote service and I’d rather not couple myself to a service.

In the end, I went with Seaborn (Stanford). This seemed to look the best of all of the options, even if it was tough to get some of the features working right. They recently added a chart for the exclusive purpose of plotting categorical/factor-based data: factorplot.

An example of Seaborn’s factorplot:

I put together an example of a bar-chart using data from data.gov. I used pandas to read the CSV data. Since Seaborn is built on top of matplotlib and matplotlib appears to have issues displaying graphics in my local environment, I had to rely on running the example via ipython using the matplotlib magic function (which loads everything necessary and worked as expected).

To run the example, you’ll need the following packages (in addition to the ipython environment):

- pandas

- numpy

- seaborn

- matplotlib

The code:

# Tell ipython to load the matplotlib environment.

%matplotlib

import itertools

import pandas

import numpy

import seaborn

import matplotlib.pyplot

_DATA_FILEPATH = 'datagovdatasetsviewmetrics.csv'

_ROTATION_DEGREES = 90

_BOTTOM_MARGIN = 0.35

_COLOR_THEME = 'coolwarm'

_LABEL_X = 'Organizations'

_LABEL_Y = 'Views'

_TITLE = 'Organizations with Most Views'

_ORGANIZATION_COUNT = 10

_MAX_LABEL_LENGTH = 20

def get_data():

# Read the dataset.

d = pandas.read_csv(_DATA_FILEPATH)

# Group by organization.

def sum_views(df):

return sum(df['Views per Month'])

g = d.groupby('Organization Name').apply(sum_views)

# Sort by views (descendingly).

g.sort(ascending=False)

# Grab the first N to plot.

items = g.iteritems()

s = itertools.islice(items, 0, _ORGANIZATION_COUNT)

s = list(s)

# Sort them in ascending order, this time, so that the larger ones are on

# the right (in red) in the chart. This has a side-effect of flattening the

# generator while we're at it.

s = sorted(s, key=lambda (n, v): v)

# Truncate the names (otherwise they're unwieldy).

distilled = []

for (name, views) in s:

if len(name) > (_MAX_LABEL_LENGTH - 3):

name = name[:17] + '...'

distilled.append((name, views))

return distilled

def plot_chart(distilled):

# Split the series into separate vectors of labels and values.

labels_raw = []

values_raw = []

for (name, views) in distilled:

labels_raw.append(name)

values_raw.append(views)

labels = numpy.array(labels_raw)

values = numpy.array(values_raw)

# Create one plot.

seaborn.set(style="white", context="talk")

(f, ax) = matplotlib.pyplot.subplots(1)

b = seaborn.barplot(

labels,

values,

ci=None,

palette=_COLOR_THEME,

hline=0,

ax=ax,

x_order=labels)

# Set labels.

ax.set_title(_TITLE)

ax.set_xlabel(_LABEL_X)

ax.set_ylabel(_LABEL_Y)

# Rotate the x-labels (otherwise they'll overlap). Seaborn also doesn't do

# very well with diagonal labels so we'll go vertical.

b.set_xticklabels(labels, rotation=_ROTATION_DEGREES)

# Add some margin to the bottom so the labels aren't cut-off.

matplotlib.pyplot.subplots_adjust(bottom=_BOTTOM_MARGIN)

distilled = get_data()

plot_chart(distilled)

To run the example, save it to a file and load it into the ipython environment. If you were to save it as “barchart.ipy” (using the “ipy” extension so it processes the %matplotlib directive properly) and then start ipython using the “ipython” executable, you’d load it like this:

%run barchart.ipy

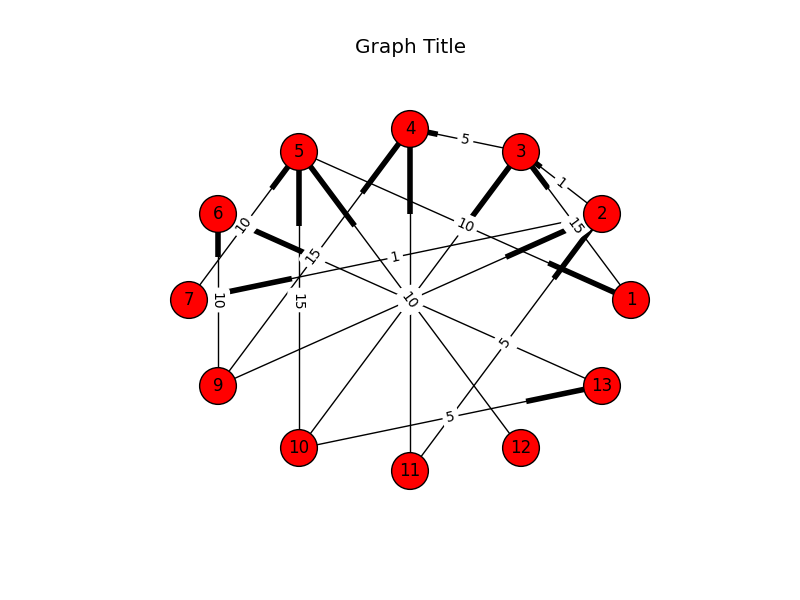

The graphic will be displayed in another window:

I should also mention that I really like pygal but didn’t consider it an option because I wanted a traditional, flat image, not an SVG. Even so, here’s an example from their website:

import pygal # First import pygal

bar_chart = pygal.Bar() # Then create a bar graph object

bar_chart.add('Fibonacci', [0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55]) # Add some values

bar_chart.render_to_file('bar_chart.svg') # Save the svg to a file

Output:

Notice that the resulting SVG even has hover effects.

You must be logged in to post a comment.